A Fuzzy Workaround for Roe v. Wade

Why did the Catholic Church wait until 1992 to pardon Galileo? Answer: the Pope is no mere president, the Church hierarchy no mere Congress. They cannot simply change opinion. They derive their authority from a higher, infallible authority. To admit error, is to question the Church’s connection to the higher authority, and thus undermine the institution. The Supreme Court is in a similar position. The Court is no mere legislature, free to change its mind through personnel turnover or popular demands. The Court seeks Truth, the meaning of the Constitution. At the very least, it must maintain the pretense that it is seeking this Truth vs. legislating from the Bench.

In other words, put not your hope in a wholesale overthrow of Roe v. Wade by electing a long succession of religious conservative Presidents and senators to achieve a brute force alignment of the Court. Whereas this dream serves the Republican Party well, it is too weak a strategy for the cause of life. Not only is an unbroken string of social conservative Presidents long enough to outlive the liberal Justices unlikely, even the Republican appointees are problematic. The appointees must not only be socially conservative, they must be so hardcore that they are willing to undermine the institution that they are being appointed to lead for the good of the greater cause.

Such people are hard to get past the Senate.

While popular will and electoral politics play important roles, actions in these arenas are not enough. The Court needs a means to save face. I think I have found one.

Admittedly I am not a lawyer and I don’t play one on TV, but I can read a legal ruling and follow its logic. More importantly, I have some acquaintance with some modern philosophical tools which have yet to make it into the legal mainstream, but could be added. The strategy I am about to propose is thus not ready for a run through the courts yet. The ideas need to be first discussed and debated by the political and legal elite. Though this is no quick process, it is still faster than waiting for that unbroken string of socially conservative Presidents.

The Logic of Roe v. Wade

Study Justice Blackmun’s lead up to his decision. His logic is very similar to my call for using fuzzy logic to achieve a democratic consensus on the abortion issue. It is only at the end of his derivation that he cops out and draws a pair of sharp dividing lines. His proof-by-ignorance near the end resembles Murray Rothbard’s proof-by-ignorance for anarchy. (We cannot read minds; therefore, we must rely entirely upon revealed preference for social utility maximization.) This cop out begs for future investigation, a process that validates the Court as an institution. While those of us who favor abortion restrictions should pursue such a reinvestigation when there is a conservative majority on the Bench, it need not be a super majority and the conservative Justices need not be radical. We might even sway a liberal Justice or two.

Let us now walk through Blackmun’s logic in more detail. Starting in Article VI he claims that the abortion laws being challenged were not all that old:

It perhaps is not generally appreciated that the restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a majority of States today are of relatively recent vintage. Those laws, generally proscribing abortion or its attempt at any time during pregnancy except when necessary to preserve the pregnant woman's life, are not of ancient or even of common law origin. Instead, they derive from statutory changes effected, for the most part, in the latter half of the 19th century. [p130]

He then walks through time showing the many differences of opinion on the subject. In ancient times the Persians punished abortion severely while the ancient Greeks and Romans allowed it – despite Hippocrates’ admonitions against abortion. Under English common law, a fetus wasn’t considered alive until “quickening.”

3. The common law. It is undisputed that, at common law, abortion performed before "quickening" -- the first recognizable movement of the fetus in utero, appearing usually from the 16th to the 18th week of pregnancy pregnancy [n20] -- was not an indictable offense.. [n21] The absence [p133] of a common law crime for pre-quickening abortion appears to have developed from a confluence of earlier philosophical, theological, and civil and canon law concepts of when life begins. These disciplines variously approached the question in terms of the point at which the embryo or fetus became "formed" or recognizably human, or in terms of when a "person" came into being, that is, infused with a "soul" or "animated." A loose consensus evolved in early English law that these events occurred at some point between conception and live birth.. [n22] This was "mediate animation." Although [p134] Christian theology and the canon law came to fix the point of animation at 40 days for a male and 80 days for a female, a view that persisted until the 19th century, there was otherwise little agreement about the precise time of formation or animation. There was agreement, however, that, prior to this point, the fetus was to be regarded as part of the mother, and its destruction, therefore, was not homicide. Due to continued uncertainty about the precise time when animation occurred, to the lack of any empirical basis for the 40-80-day view, and perhaps to Aquinas' definition of movement as one of the two first principles of life, Bracton focused upon quickening as the critical point. The significance of quickening was echoed by later common law scholars, and found its way into the received common law in this country.

He then moves on to English statutory law which had a penalty function with increasing penalties as the pregnancy progressed.

4. The English statutory law. England's first criminal abortion statute, Lord Ellenborough's Act, 43 Geo. 3, c. 58, came in 1803. It made abortion of a quick fetus, § 1, a capital crime, but, in § 2, it provided lesser penalties for the felony of abortion before quickening, and thus preserved the "quickening" distinction. This contrast was continued in the general revision of 1828, 9 Geo. 4, c. 31, § 13. It disappeared, however, together with the death penalty, in 1837, 7 Will. 4 & 1 Vict., c. 85. § 6, and did not reappear in the Offenses Against the Person Act of 1861, 24 & 25 Vict., c. 100, § 59, that formed the core of English anti-abortion law until the liberalizing reforms of 1967. In 1929, the Infant Life (Preservation) Act, 19 & 20 Geo. 5, c. 34, came into being. Its emphasis was upon the destruction of "the life of a child capable of being born alive." It made a willful act performed with the necessary intent a felony. It contained a proviso that one was not to be [p137] found guilty of the offense

unless it is proved that the act which caused the death of the child was not done in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother.

And then he moved on to early American law:

5. The American law. In this country, the law in effect in all but a few States until mid-19th century was the preexisting English common law. Connecticut, the first State to enact abortion legislation, adopted in 1821 that part of Lord Ellenborough's Act that related to a woman "quick with child." ." [n29] The death penalty was not imposed. Abortion before quickening was made a crime in that State only in 1860.. [n30] In 1828, New York enacted legislationlegislation [n31] that, in two respects, was to serve as a model for early anti-abortion statutes. First, while barring destruction of an unquickened fetus as well as a quick fetus, it made the former only a misdemeanor, but the latter second-degree manslaughter. Second, it incorporated a concept of therapeutic abortion by providing that an abortion was excused if it

shall have been necessary to preserve the life of such mother, or shall have been advised by two physicians to be necessary for such purpose.

Let us pause here and note the similarities between Blackmun’s logic to this point and my own call for applying fuzzy logic to the start of human life. First, Blackmun notes the differences of opinion on the subject going back to ancient times. Second, Blackmun observes that from the Middle Ages era up until the American Civil War, early abortion was either legal or not punished as much as later term abortions. My call for some type of ramp function for punishment for abortion is thus in keeping with common law legal traditions. Using a democratic process to derive this ramp function embraces the uncertainties and differences of opinion on the subject.

Anyway, back to the story. Blackmun moves on to show that the distinction between conception and quickening disappeared later, and that the strict abortion laws of the type being challenged were relatively modern:

By 1840, when Texas had received the common law,, [n32] only eight American States [p139] had statutes dealing with abortion.. [n33] It was not until after the War Between the States that legislation began generally to replace the common law. Most of these initial statutes dealt severely with abortion after quickening, but were lenient with it before quickening. Most punished attempts equally with completed abortions. While many statutes included the exception for an abortion thought by one or more physicians to be necessary to save the mother's life, that provision soon disappeared, and the typical law required that the procedure actually be necessary for that purpose. Gradually, in the middle and late 19th century, the quickening distinction disappeared from the statutory law of most States and the degree of the offense and the penalties were increased. By the end of the 1950's, a large majority of the jurisdictions banned abortion, however and whenever performed, unless done to save or preserve the life of the mother.. [n34] The exceptions, Alabama and the District of Columbia, permitted abortion to preserve the mother's health.. [n35] Three States permitted abortions that were not "unlawfully" performed or that were not "without lawful justification," leaving interpretation of those standards to the courts.. [n36] In [p140] the past several years, however, a trend toward liberalization of abortion statutes has resulted in adoption, by about one-third of the States, of less stringent laws, most of them patterned after the ALI Model Penal Code, § 230.3,, [n37] ] set forth as Appendix B to the opinion in Doe v. Bolton, post, p. 205.

It is thus apparent that, at common law, at the time of the adoption of our Constitution, and throughout the major portion of the 19th century, abortion was viewed with less disfavor than under most American statutes currently in effect. Phrasing it another way, a woman enjoyed a substantially broader right to terminate a pregnancy than she does in most States today. At least with respect to the early stage of pregnancy, and very possibly without such a limitation, the opportunity [p141] to make this choice was present in this country well into the 19th century. Even later, the law continued for some time to treat less punitively an abortion procured in early pregnancy.

Laws against abortion grew harsher during the late 1800s than they were during the founding of this country – and the adoption of our Constitution. One might argue based on the Roe decision up to this point that going back to the earlier abortion laws might be constitutional. I won’t limit the argument to that, but it is worth pondering. Anyway, Blackmun in Article VII Blackmun lists three possible reasons for the harsher abortion laws in the late 1800s:

- To discourage illicit sex; i.e., an extension of Victorian mores.

- To protect the health of the mother, since abortion was dangerous at the time.

- To protect the unborn, including potential life.

Blackmun correctly notes that the first justification was obsolete at the time of Roe v. Wade. Sexual mores had loosened considerably (and they remain loose to this day). The second justification remains, but only after the first trimester. Surgical procedures have improved greatly; we now have antiseptics and antibiotics! Still, at the time of Roe abortion after the first trimester was more dangerous than childbirth so Blackmun upheld anti abortion law after the first trimester for this reason. The third reason, to protect the unborn still holds! Blackmun wrote [boldface mine]:

The third reason is the State's interest -- some phrase it in terms of duty -- in protecting prenatal life. Some of the argument for this justification rests on the theory that a new human life is present from the moment of conception.. [n45] ] The State's interest and general obligation to protect life then extends, it is argued, to prenatal life. Only when the life of the pregnant mother herself is at stake, balanced against the life she carries within her, should the interest of the embryo or fetus not prevail. Logically, of course, a legitimate state interest in this area need not stand or fall on acceptance of the belief that life begins at conception or at some other point prior to live birth. In assessing the State's interest, recognition may be given to the less rigid claim that as long as at least potential life is involved, the State may assert interests beyond the protection of the pregnant woman alone. [p151]

Whoa! Privacy does not trump the rights of the unborn! We do not need to refute “emanations and penumbras.” We can have anti abortion laws and privacy rights implied by the Constitution. Blackmun repeats in Article VIII [boldface mine]:

On the basis of elements such as these, appellant and some amici argue that the woman's right is absolute and that she is entitled to terminate her pregnancy at whatever time, in whatever way, and for whatever reason she alone chooses. With this we do not agree. Appellant's arguments that Texas either has no valid interest at all in regulating the abortion decision, or no interest strong enough to support any limitation upon the woman's sole determination, are unpersuasive. The [p154] Court's decisions recognizing a right of privacy also acknowledge that some state regulation in areas protected by that right is appropriate. As noted above, a State may properly assert important interests in safeguarding health, in maintaining medical standards, and in protecting potential life. At some point in pregnancy, these respective interests become sufficiently compelling to sustain regulation of the factors that govern the abortion decision. The privacy right involved, therefore, cannot be said to be absolute. In fact, it is not clear to us that the claim asserted by some amici that one has an unlimited right to do with one's body as one pleases bears a close relationship to the right of privacy previously articulated in the Court's decisions. The Court has refused to recognize an unlimited right of this kind in the past. Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 11 (1905) (vaccination); Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927) ( sterilization).

We, therefore, conclude that the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified, and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.

And again [boldface mine]:

Although the results are divided, most of these courts have agreed that the right of privacy, however based, is broad enough to cover the abortion decision; that the right, nonetheless, is not absolute, and is subject to some limitations; and that, at some point, the state interests as to protection of health, medical standards, and prenatal life, become dominant. We agree with this approach.

Prenatal life trumps privacy! So how did the court end up defending abortion? Answer: the right to abortion comes from the uncertainty as to when life begins. From Article IX:

Texas urges that, apart from the Fourteenth Amendment, life begins at conception and is present throughout pregnancy, and that, therefore, the State has a compelling interest in protecting that life from and after conception. We need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man's knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer. [p160]

It should be sufficient to note briefly the wide divergence of thinking on this most sensitive and difficult question. There has always been strong support for the view that life does not begin until live' birth. This was the belief of the Stoics.. [n56] It appears to be the predominant, though not the unanimous, attitude of the Jewish faith.. [n57] It may be taken to represent also the position of a large segment of the Protestant community, insofar as that can be ascertained; organized groups that have taken a formal position on the abortion issue have generally regarded abortion as a matter for the conscience of the individual and her family.. [n58] As we have noted, the common law found greater significance in quickening. Physician and their scientific colleagues have regarded that event with less interest and have tended to focus either upon conception, upon live birth, or upon the interim point at which the fetus becomes "viable," that is, potentially able to live outside the mother's womb, albeit with artificial aid.. [n59] Viability is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks.. [n60] The Aristotelian theory of "mediate animation," that held sway throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe, continued to be official Roman Catholic dogma until the 19th century, despite opposition to this "ensoulment" theory from those in the Church who would recognize the existence of life from [p161] the moment of conception.. [n61] ] The latter is now, of course, the official belief of the Catholic Church. As one brief amicus discloses, this is a view strongly held by many non-Catholics as well, and by many physicians. Substantial problems for precise definition of this view are posed, however, by new embryological data that purport to indicate that conception is a "process" over time, rather than an event, and by new medical techniques such as menstrual extraction, the "morning-after" pill, implantation of embryos, artificial insemination, and even artificial wombs. . [n62]

Take special note of the boldfaced passage above. The court admits incompetence in establishing when life begins. We can use this. Here we have the seeds of the error in the final decision.

Article X gives the reason for overruling the Texas law [boldface mine]:

In view of all this, we do not agree that, by adopting one theory of life, Texas may override the rights of the pregnant woman that are at stake. We repeat, however, that the State does have an important and legitimate interest in preserving and protecting the health of the pregnant woman, whether she be a resident of the State or a nonresident who seeks medical consultation and treatment there, and that it has still another important and legitimate interest in protecting the potentiality of human life. These interests are separate and distinct. Each grows in substantiality as the woman approaches [p163] term and, at a point during pregnancy, each becomes "compelling."

The Texas law, which banned all abortions, was unconstitutional because it adopted one theory of life despite wide divergence of opinion on the subject. The Court acknowledged that the State’s interest in protecting the unborn grows over the course of the pregnancy.

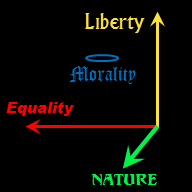

Does any of this seem familiar? It should if you read my chapters on fuzzy logic and how to apply fuzzy logic to the beginning of human life. A ramp function or other continuous curve for humanness as a function of gestation time better accounts for the uncertainties on the start of life than the Court’s final decision in Roe v. Wade.

The Court’s final decision is a cop out. First, the Court upheld State interests after the first trimester based on health of the mother:

With respect to the State's important and legitimate interest in the health of the mother, the "compelling" point, in the light of present medical knowledge, is at approximately the end of the first trimester. This is so because of the now-established medical fact, referred to above at 149, that, until the end of the first trimester mortality in abortion may be less than mortality in normal childbirth. It follows that, from and after this point, a State may regulate the abortion procedure to the extent that the regulation reasonably relates to the preservation and protection of maternal health…

That was an easy answer because statistics were available. The second part of the ruling, however, is arbitrary!

With respect to the State's important and legitimate interest in potential life, the "compelling" point is at viability. This is so because the fetus then presumably has the capability of meaningful life outside the mother's womb. State regulation protective of fetal life after viability thus has both logical and biological justifications. If the State is interested in protecting fetal life after viability, it may go so far as to proscribe abortion [p164] during that period, except when it is necessary to preserve the life or health of the mother.

The Court previously said that it could not determine the point at which life begins. Here, it makes a decision on the matter with a one sentence proof. One could argue that viability is a starting point for the State’s interest because the State can take on the burden of its decision, vs. leaving all the burden in the hands of the mother, which needs be the case for earlier abortion restrictions. But that is not the explicit logic which led the Court to its final decision. The Court’s decision is based on the uncertainty of when human life begins, that adopting any particular group’s opinion violates the rights of the rest.

We have grounds for appeal.

Conclusion

In Roe v. Wade the Court upheld two separate criteria for when the State has an interest in restricting abortions: the health of the mother and the start of human life. The former time was earlier, the end of the first trimester, but we should expect that time to move ever later with improved medical technology, unless we who hold life sacred can make the psychological damage argument stick. The second time is more arbitrary, but was less important as it came later. But it can become more important should medical technology be deemed improved, or we successfully revisit the Court’s arbitrary compelling interest time.

The start of life is uncertain. Opinions do differ. Accepting the opinion of one group violates the rights of the others. But such uncertainties are why we have democratically elected representatives! If all law could be derived, we would need no legislatures and have law discovery by courts only. Anarchist Murray Rothbard argued for just that in The Ethics of Liberty. This was how ancient Israel was governed during the days of the Judges. Somehow I doubt the liberals on the Court have such a system in mind as their ideal, however. Modern liberals believe in democracy. We just need to come up with a better democratic mechanism for resolving the abortion question.

At least, this is what I see reading Roe v. Wade by itself. I am not a lawyer. Any lawyers in the audience? I would appreciate a critique, either in the comments below or by email.