Economics

There are values and then there are the actions needed to fulfill values. Economics is the science of how to do the latter. Ye who would rule would do well to study economics.

Intent is not enough.

Microeconomics

Let us start with the subfield of economics that’s on the soundest footing, where liberal and conservative economists frequently agree – because the logic is so compelling: microeconomics. For a very readable textbook on the field, check out David D. Friedman’s Price Theory, an Intermediate Text. Unlike many textbooks, Price Theory is not dry. It features some very untraditional examples, such as the economics of marriage and the economics of a fantasy hero fending off a horde of orcs.

But it is a textbook, and thus covers some challenging material, and has exercises. If you want something lighter, try Hidden Order, the Economics of Everyday Life. This book is basically Price Theory with the hard bits taken out.

Critiques of Microeconomics

Microeconomics is based on the premise that humans are rational – at least part of the time – and that irrational behavior is sufficiently random as to cancel out. This is a questionable premise, and psychologists have produced many counterexamples in the lab. You Are Not So Smart provides a breezy survey of these non-rational aspects of human nature. It’s quite readable, if a bit smug. (A note of caution: I have been reading rumors that quite a few of the psychology results that have made it into books such as these have not been reproduced.)

I hear the more definitive work on the subject is Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. I have not read this one, so I cannot comment on its readability. But it has sold well, so somebody likes it.

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics is a much more controversial branch of economics. There are multiple schools of thought, and adherents tend to divide along ideological grounds. (A major theme of Holistic Politics is that this is a grave error. Whereas Keynes’ theory does provide an excuse for bigger government and transfer programs, Keynes’ theory is not a necessary excuse. Providing public goods and alleviating poverty stand on their own merits. Keynes’ program also includes counterproductive subsidies to the old money rich.)

To understand the vocabulary of economics pundits on the news, you need to understand Keynesian Economics. If you are ambitious, you can take a crack at reading Keynes in his own words: The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. But prepare to be thwarted. Keynes uses a lot of dated jargon and references to other people’s works. The General Theory reads like stepping into the middle of a long running conversation. Such obscurity is appealing to those who cherish ineffable occult knowledge. But it can also hide circular arguments (and does).

For a readable exposition of Keynes’ theories, get a copy of Paul Samuelson’s Economics textbook. Unlike Keynes, Samuelson wrote very well. This was a very popular introductory text for many years, so you can find used copies all over the place. I got mine (7th edition) at a library book sale if I recall correctly. The early editions start with macroeconomics and move to microeconomics for the second semester. I don’t know about the later editions. I recommend an earlier edition as this is the book that made Keynes’ ideas go mainstream.

For a readable takedown of Keynes’ theory, try Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson. It’s a very easy read, and exposes the inherent silliness of Keynes’ Broken Window Economics within the first few chapters.

The problem with this work is that it is too easy. It is difficult to believe that intelligent people could fall for an idea that can be taken apart that easily.

If Keynes’ explanation for the Great Depression is incorrect, then what is the correct explanation? Economists of the Austrian School had an alternative, but it wasn’t very appealing for those eager to joystick the economy. Read it anyway, it’s useful even if you want more government than most in the Austrian School prefer. Mark Skousen is my preferred author on the subject. He’s readable, scientific, and plays fair (which alas, is not true for many in this school today). The Structure of Production provides an alternative to Keynes’ theory that doesn’t require one to believe in ineffable paradoxes. (Fun fact: the Keynesian model overlooks close to half of the moment’s current economic activity!)

Whether the Austrian School explanation of the business cycle is complete is another matter. Have a gander at Fred Foldvary’s Geo-Austrian Synthesis. (A web page, not a book.)

Money System Basics

Many people come to me and say: “Hey, our money is worthless!” Yet when I ask them for some of those worthless pictures of dead Presidents, they are reluctant to act on their prior assertion.

Other people believe that our money is backed up by “faith” or that the Federal Reserve System is a true private corporation with member banks collecting the hundreds of billions of dollars that the U.S. Treasury pays in interest to the Fed.

Most people don’t have a clue as to how our monetary system works. This is understandable. The system is complicated, and the terminology is deceptive. The phrase “creating money” sounds like simply printing 20 dollar bills. But that’s not what the phrase means.

Years ago I picked up a copy of Money and Banking at a library book sale. It was a very good impulse buy. Those who would reform the banking system should have textbook level knowledge as to how the current system works.

The Wealth Gap

The wealth gap in the U.S. has grown so wide that socialism and fascism are on the rise. We might want to do something about it.

Thomas Piketty sounds the alarm in Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The modern left loves this book. I am not so sure. One third in I started falling asleep each night after reading just a couple of pages. Parts of this book are indeed interesting. In places he does seem to get it. In other places he seems unrealistic as to a remedy for the wealth gap (recreating the growth of the 1950s within first world nations). The book is quite uneven. In places he is interesting. In other places he expands a page worth of material into 20. Despite the overall verbosity, he skimps on explanations on how he computes various tables and graphs.

For a much better analysis of the wealth gap, read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. That’s right, Adam Smith was a liberal. He was attacking the rentier class of his day. Thanks to 2 ½ centuries of language drift, this book is a bit of a challenge, but it is readable. Smith starts from first principles vs. citing other people’s arguments expecting you to have read them. Jargon is limited to commercial terms of his day (some of which have somewhat different meaning today). Within this book you will find remedies to lower the rate of business profits and raise worker incomes – which have nothing to do with unions, labor laws or minimum wage mandates.

Get a large paperback or hardback edition of this work. It takes a while to read. (My copy is a mass market paperback from college days. Way too small!)

In the interest being fair and balanced, let me throw in a couple of works that celebrate the wealth gap. The first is Superwealth by Max Borders. Max is the most anti-envious person I know. This book provides a wide array of arguments for leaving the rich alone and enjoying the fruits of capitalism. Some of the arguments are pretty good, others are a bit of a stretch.

A more mainstream argument can be found in Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond. The primary thrust of this book is to counter modern racists, to provide a non-genetic explanation for why some nations achieved civilization and technology long before others. He reveals many geographic factors that led some areas to become civilized while others stayed primitive. However, a repeated motif within his book is that concentrations of wealth – either private or government – allow the start of capital intensive technologies. Worth considering before going overboard on the redistribution.

The History of Economics

The Worldly Philosophers is perhaps the most well known popular history of economics. It’s been a while since I read it, but I recall it was pretty good.

But it is also incomplete. Some important players are missing.

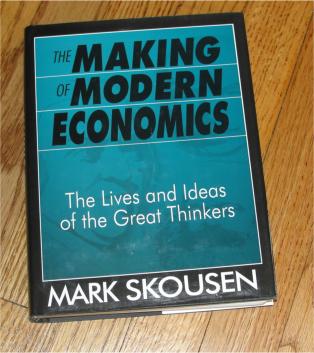

Mark Skousen has written a more up to date history of the subject, including both more modern developments as well as some thinkers overlooked by Heilbronner (i.e., the Austrian School). Skousen is of the Austrian School, but unlike like many in this school, Skousen plays fair. This is a fun read, with lots of juicy stories.

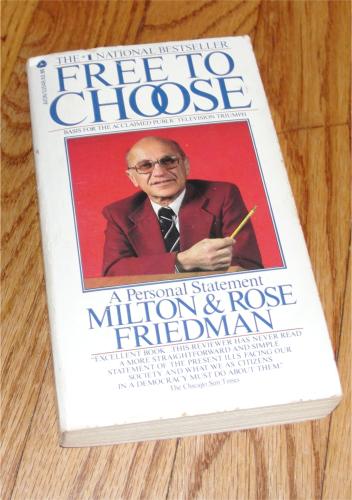

Economics on PBS

Way back in the days of high inflation and polyester leisure suits, PBS ran Free to Choose, a series of video essays by Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman. After Dr. Friedman makes his case in each episode, a panel of politicians and economists of differing viewpoints asks pointed questions and makes rebuttals. It is a model of civil debate from a more civil time. Milton and his wife Rose published a book of the same title/subject matter around the same time. I know not which came first. I recommend both the book and the videos. They are models of science, civility, and pragmatic thinking covering subjects where these qualities are often missing these days.